The Burnout Series, Part 3: Burnout Prevention

Other resources you may like:

Evaluate your life satisfaction (self-assessment)

3-week burnout recovery plan (self-paced guide)

Burnout is a modern-day epidemic in the workplace, and the effects of burnout can be long-lasting and devastating on a person’s personal mental and physical health, career, and relationships, too.

How can we prevent burnout from occurring?

This essay provides a whole host of tips for individuals to prevent work burnout. You can also read about how to prevent burnout at the manager and organizational level.

This essay is also part 3 of a series on burnout, continuing on from two previous essays. Read part 1: Burnout Symptoms for more fundamental burnout learnings and part 2: Burnout Recovery for active burnout recovery tips. Also, go to Learn About Burnout to find an extensive list of resources for recovery/prevention, and read firsthand stories from people who have experienced it.

Before diving into the details of burnout prevention, it’s important to note a few key points:

Everyone is susceptible to burnout, and high-achievers are especially so. The risks of burnout can be easily dismissed by high-achievers, who through the act of achieving greatly, become used to pushing greatly in order to achieve. People who become high performers can become desensitized to discomfort/pain, which can either create a dangerously false sense of being immune to burnout, or a mis-diagnosis of burnout symptoms as simply a blip on the journey or one more mental obstacle to overcome.

The risks of burnout MUST be taken seriously — burnout — and any other, stress-related mental health disorder— is a very serious condition which can have a years-long recovery period and dire health risks. When it comes to consequences, burnout is not simply a matter of will or “mind over matter.”

Burnout prevention involves learning how to listen to the body. Burnout is a physiological condition. The advanced stages of burnout (“burnout syndrome” is a recognized medical condition) involve pushing the body past its limits, which trips a brain circuit breaker that can cause a mental or physical collapse; this is the body’s last resort when the mind has chronically disregarded the health of the body. Tuning into your body’s needs is therefore central to being able to prevent burnout from setting in in the first place, as well as in preventing a progression into the advanced stages.

4 categories of tips for individuals to prevent burnout

When it comes to preventing burnout at an individual level, here are four categories to focus on:

Managing stress and the health of your body

Your workload

Your work-reward mix

Your mental narratives

Preventing burnout by focusing on your body

One of the most common issues that can cause a burnout is an interruption in the body’s ability to regulate its own health. This is a broad brush that can mean many different things, but in practical burnout terms, can be scoped to preventative focus on self care activities.

The various activities that fall into the umbrella term, “self care” are very important for the body’s ability to manage its own health, by enabling your body to physically rest and recover from the mental/emotional/physical exertion of work.

Among the top of the list of important self care activities are sleep and taking time off from work.

Sleep

Neuroscientist and sleep expert Matthew Walker covers the relationship between sleep and both bodily and cognitive health in his book, Why we Sleep. Among the extensive list of facts shared are included:

Sleeping less than 7 hours per night is actually quite damaging to our health. Our bodies need 7–9 hours per night (hence the common reference of 8 hours) in order to be fully rested. This doesn’t mean laying in bed, either; this means 7–9 hours of actual sleep.

Our bodies also need a good quality of sleep (i.e. not waking often throughout the night), and enough of both types of sleep. During sleep, we experience both non-rapid eye movement (NREM) and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep phases. Both are important to recovering and functioning at our best, but getting sufficient REM sleep (which occurs later in our sleep cycle and can be disrupted by going to bed late and waking up early) is especially pivotal for learning, memory, creativity.

Walker debunks the idea of being able to pay down “sleep debt” by sleeping more hours later. If we sleep only 5 hours one night, we cannot repair the damage done by sleeping 11 hours another night to achieve an average of 8 hours per night.

Time off from work

Taking time off from work is also important for enabling us to rejuvenate our minds and allow our brains to recover from working.

During (quality) time off from work, because we are not exposed to the many stressors we normally would be during work, our stress levels have a better chance to lower, wherein our body can do the work of repairing the damage done by stress.

Yet, many people either neglect to take time off, feel as though it is not accessible (see the mental narratives section below), or else don’t fully unplug from work during time off.

To be clear: taking time fully off from work regularly is essential to burnout prevention.

A LinkedIn poll on vacation habits I ran

Completing the stress cycle

As touched on in “time off” above, a key outcome of self care is healthy management of stress. Unmitigated accumulation of stress is one of the main factors leading to burnout.

Burnout researchers Amelia and Emily Nagoski explain in their book, Burnout, that stress management involves a process she terms “completing the stress cycle.”

Their research points to the fact that stress (and burnout) are not just mental, but physiological phenomenons. Stress triggers (e.g. work meetings, deadlines, client emails, etc.) initiate the body’s stress-response system (also known as the fight/flight/freeze mode), which pumps stress hormones into our bodies to deal with the stressor at hand.

The two problems are that:

Our bodies are not meant to remain in stress response mode (chronic stress wears our bodies out and breaks them down)

Simply mentally dealing with the stressor (i.e. replying to the email/deadline or making it through the meeting) is not enough for our bodies to shift out of stress response mode

Beyond dealing with the stressor, it takes additional, and particular physiological actions to “complete the stress cycle.” Without these actions, our stress levels can become chronically elevated, and this physiological, chronic stress state inhibits the body’s ability to rest and recover, which causes us to become at risk of burnout.

Consider the following additional self care tips which can help your body stay healthy by completing the stress cycle on a regular basis each day/week:

Body movement or exercise, such as cardio (using your muscles is the original reason for the stress buildup, but be sure to either not skip the cool down or also do one of the other actions below, in order to signal to your body it’s also time to rest and recover)

Tensing and releasing all of your muscles

Stretching, yoga, or deep breathing

Going for a walk in nature

A good laugh (joking with friends or seeing a comedy show really is medicine!)

Spending time with other people including partners, friends, family, neighbors, co-workers, clubs, and religious groups

Even spending time with animals can help your body complete its stress cycles

Getting quality sleep, as touched on above, can also be a key factor in completing your body’s stress cycles

Preventing burnout by focusing on your workload

When our workload becomes overwhelming or unsustainable, it naturally creates the conditions for burnout. Most people don’t (consciously) seek out an unsustainable workload, and so reducing workload can be one of the most tricky burnout risk factors to address, as it entails influencing external circumstances, all of which are outside of an individual’s sphere of control, or even influence.

That said, it is always possible to reduce workload, at least a little bit. Here are some tips for reducing workload:

Explore the bounds of what workload decisions are within your sphere of control/influence, and exercise what options you can control to reduce workload

Explore what workload can be eliminated, shared or put on pause — even if it is only for a temporary period of time, this can be key during critical stretches of high stress

Resist over-extending yourself in optional work areas. For instance, this involves holding back the urge to go the extra mile or raising ideas that would create more work/change when you are beginning to see the warning signs of burnout

Strengthen your resolve to ask for help, respectfully say no, and negotiate/compromise to make your overall commitments more manageable

Strengthen your delegation, prioritization, and time management skills

Proactively flag risks ahead of time to yourself and others to create and awareness and accountability to take preventative action

Draw a firm work-non-work line wherever possible: establish non-negotiable work boundaries and practice psychological detachment/mindfulness (AKA learning to detach from and let work go once the workday is over)

Work with a mentor/career coach to sharpen your workload management skills

Even when there is a true intrinsic desire at the core of an intense workload (such as for caregivers, parents, or medical school residents), workload can become unavoidably overwhelming.

In this case, is even more important to lean into self care routines and manage mental narratives (below), which can minimize the physiological/psychological effects of an overwhelming workload.

But again, no matter whether the workload is unavoidable or not, it is always possible to reduce workload some, and in the case of burnout prevention, even a little bit can help.

Preventing burnout by focusing on your work-reward mix

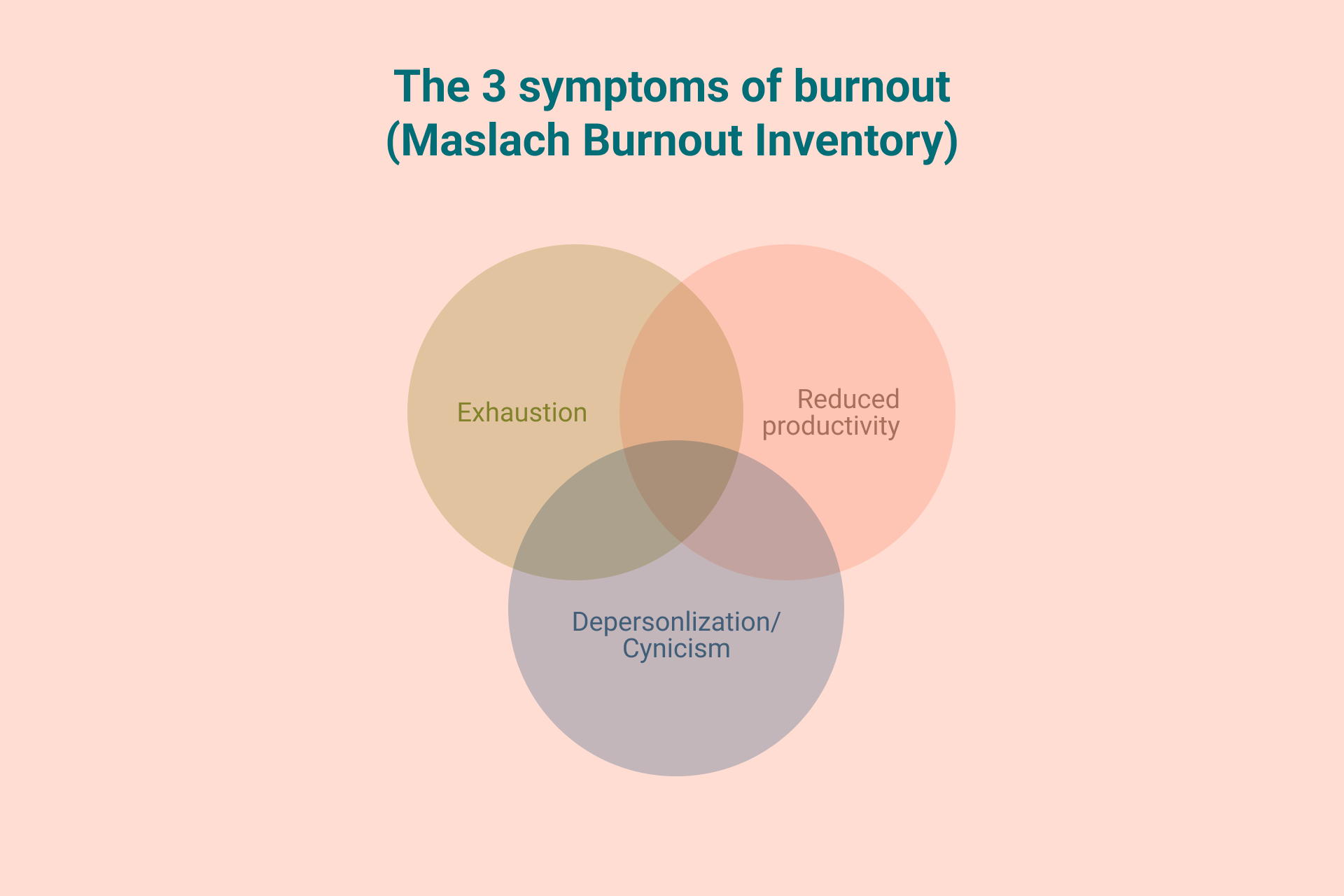

While physiological health and workload are the two most commonly explored risk factors in burnout, a lack of reward for one’s work can lead to cynicism, which is one of the 3 main criteria in diagnosing burnout (alongside emotional exhaustion and reduced efficacy).

Here are some tips to raise the level of reward that you receive from your work:

Do an objective analysis of the work you are doing to identify whether particularly intense work you don’t find rewarding is still necessary. This is useful because sometimes we continue to do work by way of momentum — only because we’ve always done it — even though it may not be as valuable as it used to or even needed at all any longer

Explore the concept of job crafting, which involves adjusting your job tasks, relationships, and job meaning

Change your role to more closely align your skillset with work that is more rewarding and aligned with your personal values

Look for ways to collaborate more with others, or otherwise increase your social interactions with others during work hours. Find more situations to work with people whom you appreciate

Try bartering work with others, looking for ways to trade work that you don’t enjoy to someone else in exchange for work you do enjoy more

Explore how cognitive reframing can enable you perceive the same, less-rewarding work in a more appreciative, or rewarding light

Reduce your reliance on work for your sense of reward. Pick up new pursuits, new hobbies, creative outlets, and expand/deepen your relationships

Develop your understanding of your own values system and worldview in order to more accurately know how to increase your sense of reward from life

Importantly, if you find yourself in a toxic workplace and have reason to believe that the culture will not change, your best option is likely to remove yourself from this workplace. Even if it means compromising on something else such as compensation, I personally urge you to choose not compromise on your personal and mental health.

Preventing burnout by focusing on your mental narratives

This is possibly one of the least talked about factors influencing burnout, but one of the most sinister. Mental narratives are sinister because our minds initially develop them with the intention of increasing our chances of surviving and success in society and work, and so they are rationalized as always being good/necessary for us.

Over time, our minds connect these narratives as the underlying cause of positive outcomes that happen to us, and connect a non-alignment with these narratives as the underlying cause of any negative outcomes which befall us. This strengthens the sense of validity these narratives hold, which can become quite unconscious, and hide the harmful consequences resulting from an over-entrenchment of these narratives.

In other words, while these narratives are established on a grain of helpfulness, when the narratives become overly ingrained, they can drive us to obsessive, insatiable behaviors which ultimately do us harm.

Why are we so critical on ourselves? Our minds have a strong drive to accumulate (accumulation is the purpose of the ego mental organ) and also a negativity bias (it takes 5 positive events to outweigh 1 negative one), which both have evolutionary advantages, yet create a disadvantage in the realm of self-actualization and happiness.

Examples of sinister mental narratives include:

Perfectionism

Imposter syndrome

Not wanting to disappoint others

Fear of failure

Here are some tips for minimizing the harmful impact of mental narratives:

Integrate life losses and process emotions when they arise: take time to grieve, mourn, be sad, be angry, rather than suppressing emotions, which can lead to using work as an escape from such unprocessed emotions

Work with a therapist to identify, understand, and weaken self-harming narratives

Practice affirmations and self-acceptance/kindness/compassion to offer an alternative to harmful narratives

Practice meditation, mindfulness, or try Positive Intelligence program’s “PQ reps” to increase your mental self-command muscles and reduce the ability of mental narratives from taking you over and perpetuating harmful, obsessive behaviors

If you are personally struggling with burn-out, remember:

You are not alone.

You are not damaged goods.

You do not need to be ashamed.

You can make it through this.

Burnout is a serious and complex issue, and everyone’s recovery journey is different. Continue your recovery with these additional steps:

Start the free, self-guided 3-week recovery plan

Read stories from people who have burned out discover burnout resources at LearnAboutBurnout.com

Explore how working with a Burnout coach can help

Take this confidential self-assessment to evaluate your current level of burnout