What William Shakespeare means by "There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so”

Other resources you may like:

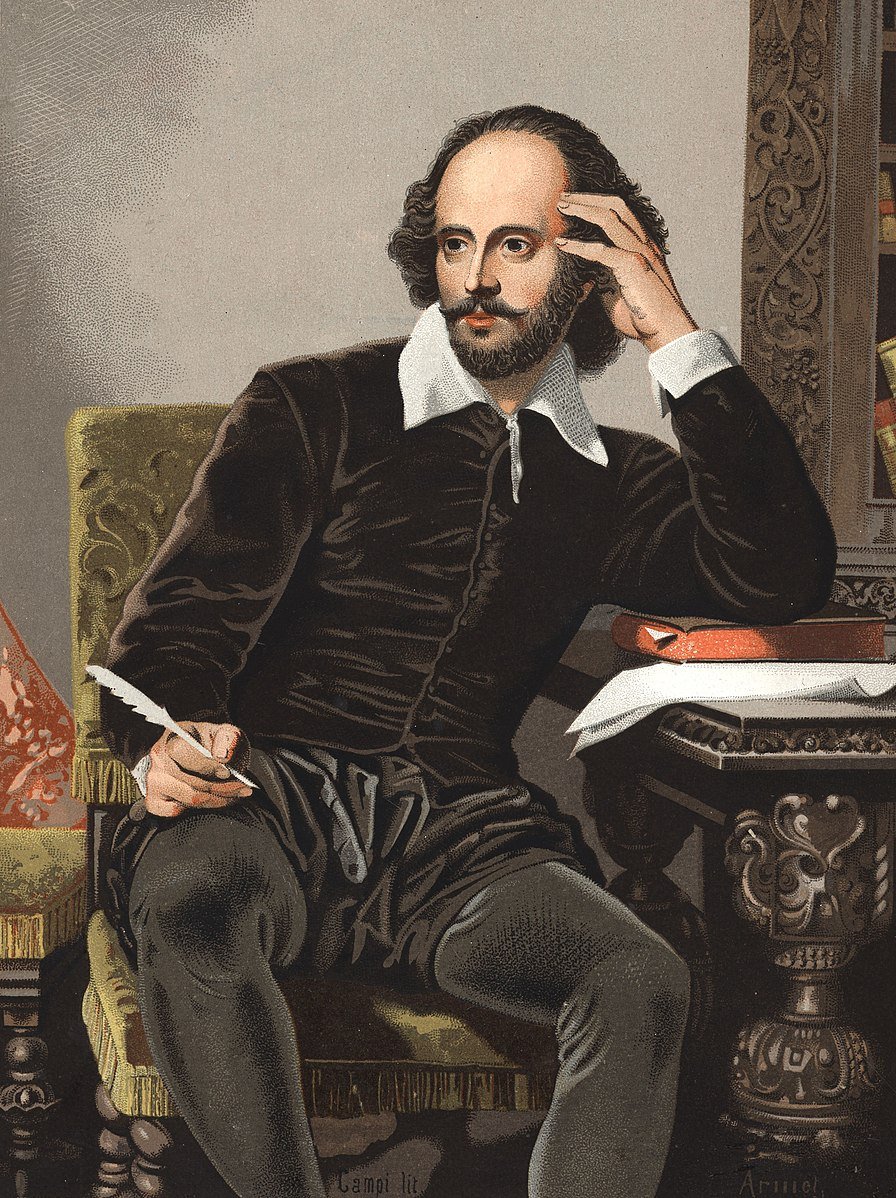

What did one of history’s great authors, William Shakespeare, mean when he penned the following sentence?

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” – William Shakespeare

The line occurs in his play, Hamlet, during an exchange between the characters Hamlet, Guildenstern, and Rosencrantz. At the time of the quote Hamlet has called the country of Denmark a prison and the three are in a disagreement over whether or not Denmark really is a prison. Hamlet believes it is, while the other two disagree.

What does it mean for there to be nothing good nor bad, but for things to be made good or bad by the thinking mind?

For millennia, philosophers have repeated this same wisdom in different words, with the hopes of empowering us with wisdom that can help us to live more peaceful, happier, and fulfilled lives.

The quote, “ignorance is bliss,” by Publilius Syrus is also apt as a synonymous quote to Shakespeare’s.

The modern-day philosopher, Eckhart Tolle also shares an anecdote that illustrates how what we think of as good or bad cannot really be labeled as such.

One day a wise man won an expensive car as a result of a lottery.

His family and friends were very happy for him and wanted to celebrate the good happening. “You’re so lucky!”’ they cheered.

The man simply smiled and said ‘Maybe.’

For a little while, he enjoyed driving the car. Then one day a drunken driver crashed into his car and he ended up in the hospital. His family and friends came to see him and lamented, ‘That was really unfortunate.’

The man simply smiled and said, ‘Maybe.’

One night while he was still in the hospital, there was a landslide and his house on the hill suddenly crashed into the sea. Again his friends and family came and exclaimed, ‘Weren’t you lucky to have been here in hospital?’

Once more, the man simply smiled and said, ‘Maybe.’

The reality that William Shakespeare, Publilius Syrus, Eckhart Tolle, and countless other philosophers point to is that we really don’t have the knowledge to say that certain events really are good or bad, and moreover that labeling things as good or bad and getting worked up about the “goodness” or “badness” really isn’t conducive to living more peaceful, happier, and fulfilled lives.

Human society invented such labels with helpful intentions. Establishing a common understanding of what is helpful and not helpful to human society helped establish laws, norms, values and mores that were aimed at reducing the occurrences of what we commonly label as good and bad.

That said, labeling events cannot control the world and make only good things happen or prevent bad things. However helpful in some cases, there will be others where the act of labeling in others will create life-limiting, obsessive behaviors in others. How does labeling limit our ability to live more peaceful, happier, and fulfilled lives?

This is because the act of subjective labeling events carries with it a risk: once we label something as good or bad, it’s hard to focus only on the objective learning from the experience. Rather, we tend to just think about the goodness or badness of the event.

If someone on the street bumps into you and calls you a name before hurrying on, are you more likely to think about walking more carefully in the future, or do you spend the rest of the day simply being upset about that encounter?

If you fail a test, what’s the likelihood that you will acknowledge your failure and take it in stride by making a plan to better prepare before the next test and then go out to dinner with friends, having applied the lesson? How many hours will you spend beating yourself up and lamenting the fact that you failed? Does that change the fact that you failed or help motivate you to do better next time?

If you get into a fight with your significant other, how prone to keeping the fight going in your mind are you? Does it make you more or less likely to tell your partner you’re sorry or forgive them and talk through why the fight happened to understand the other better? Isn’t it more interesting for your mind to make the other person - or yourself - a bad person, and to play a movie reel in your mind about the fight and cast a hue of badness over everything they do for the next week?

The perceived goodness/badness of the event is like the dessert of the event: very tasty and not healthy for our growth. The learning or takeaway is like the vegetable of the event: not the tasty part, but healthy for our growth.

For the human mind and the ego, subjective labels are quite fun to play with and very sticky. Our minds much prefer to eat the dessert and ignore the vegetables; our egos love to obsess about good or bad things that happened in the past, or imagine good or bad things that may happen to us in the future. Unless we eat the vegetables and focus on what the event taught us, we are unlikely to engage in mental behavior that can actually help us to create more peace, happiness, and fulfillment.

Just how many hours and calories of energy that could be spent exploring new directions in life end up being spent thinking about the good and bad things that happened in the past or might happen in the future?

Rather than admit mistakes, create space for stress and pain to be released, or change our behavior we prefer to complain, rehash why we don’t need to change, and endlessly replay events in our mind’s eye. Our egos prefer to create innumerable obsessive thoughts and emotions that keep us mired in the past or anxious about the future, and distract us from focusing on what we can do in the present to actually make our lives better.

We cannot prevent or guarantee good or bad events from happening, but we can decide whether or not to label events good or bad, and furthermore whether or not we can let those events go and keep living here and now. We can learn to redirect energy away from obsessive, entangling thoughts and towards enlightening, productive thoughts.

That’s not to say that we should become cold and emotionless. When we experience loss or pain, it’s normal to experience a negative reaction and to wish that loss or pain didn’t happen. The key is to let those negative reactions go before they become entrenched and obsessive, and to not come up with new ones. Obsessing will block us from seeing the goodness that can come after what we perceive as bad events, and in extreme cases can blind us to all the good that still exists in our lives, making us feel miserable because we have been harmed by a bad event that we believe never should have happened to us.

Want more accountability to reach your goals?

Many people have things they know they need to do, but need a little help sticking with. That's why I created text-based coaching check-ins.

With text-based coaching check-ins, I'll be your accountability partner. You'll get a tracker of your goals and I'll support you with encouraging texts each week to help you stay on-track to your goals. If you get stuck, I'll coach you through it.

Try 3 weeks of check-ins for free, without commitment to continue.

By seeing Denmark as prison, Hamlet effectively labels the entire country as bad, and casts a dark cloud over anything that could possibly be good. The joy of a tasty meal, the glory of sunshine on a new Spring day, the excitement in making a new friend, even appreciating another day spent alive and not dead, - all are liable to be missed so long as the badness of Denmark is more interesting to Hamlet’s mind.

No matter how much we wish bad things wouldn’t happen, they do, and they will continue to.The only reasonable thing to do knowing that bad things will keep happening is to keep living, and learn to accept and learn from the bad in life, too.

It’s the same in reverse for good labels. When we experience something that makes us happy, it’s great to experience a positive reaction and to enjoy the thoughts and feelings that come with it. But when we label something as good, then we tend to obsess about how good it was, and how the good things we have should never leave us. That’s when thinking makes something good and builds resistance to ever losing that goodness of the event, which will corrupt us from being able to let it go when it’s time to let go. No matter how much we wish good things would stick around forever, they don’t, and they will continue to appear and change, or disappear. The only reasonable thing to do knowing that good things do not last forever is to keep living, and enjoy them while they last.

Good or bad, the only reasonable thing for us to do is to eat our vegetables and continuously stay grounded in the present, working each day with the hand we are dealt and doing what we can to live more peaceful, happier, and fulfilled lives.

Curious to know more about the meaning behind the quotes of great philosophers?

Check this interpretation of what Zen Buddhism teacher, Alan Watts, means by "trying to define yourself is like trying to bite your own teeth."